So, to pick up from where I left off in the story of Frank K. Edmondson’s career, I’d like to share a few thoughts on McDonald Observatory.

My last post reported the intellectual and labor connections between Lowell Observatory and the Department of Astronomy at Indiana University (established via W. A. Cogshall). Edmondson did the work for his Master’s thesis on the motions of the globular clusters and galactic rotation at Lowell. After finishing his thesis, he stayed on for another year at the observatory, taking plates for Clyde Tombaugh, before matriculating at Harvard University. He went to Harvard with the understanding that if he finished his Ph.D., there would be a place waiting for him at Indiana University, and that’s just how it worked out. He apparently had to choose between the new position at Indiana and a more established position at UVa. Howard Shapley counseled him to take the place that had been created for him at IU, because he felt it was more important to expand the number of astronomy posts across the academy than to settle into an established spot at UVa.

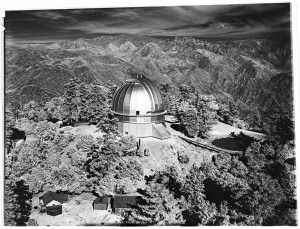

At the time, it must have seemed like a strange decision. Edmondson had been working on stellar kinematics (study of the movement of stars), so it would’ve made more sense for him to go work with Alexander Vyssotksy, who was focusing on galactic kinematics and proper motion, at Virginia. But, as we know, Edmondson had many successes at Indiana, including his role in founding a cooperative project between IU, Texas (McDonald Observatory) and Chicago. Actually, Edmondson credited Otto Struve for the start of the project, noting that Struve had published a paper calling for more cooperation in the profession.

From Edmondson’s oral history:

[Edmondson]: “If my memory’s right, Struve’s paper is to be found in the SCIENTIFIC MONTHLY. In the neighborhood of somewhere around 1938, ’39, somewhere along in there. Struve had an article called “Cooperation in Astronomy.” And his basic thesis was — “Look,” he said, “we’re training young astronomers, and then they’re going to schools where they have no telescopes at all, and something has to be done to provide them with the means to continue their scientific careers.”

“So his proposal at that time was to get some university interested in this sort of thing, and go to a foundation to get money for a second telescope at the McDonald Observatory.

“So I wrote to Struve, and asked him for two or three reprints of his article. I said, “I would like to have our President and some of the deans here read what you have written.

“So Struve sent me the reprints, and he said, “I’m also interested in getting going as fast as we can, so here’s my proposal.”

“He said that Vyssotsky had been in communication with him about doing this K star work at McDonald, and Virginia had not been able to raise the funds to pay for the telescope time that would be used for this.”

[Interviewer]: “Is this how you got into the K star work?”

[Edmondson]: “And so he said he was sure Vyssotsky would be willing to cooperate with me. So I got in touch with Vyssotsky. He said, “Oh, yes.” He said, “If you can get the telescope time, I’ll send you charts and everything.”

“So I got back to Struve. Then I got busy here — and the money was provided from here.”

[Interviewer]: “Did you start on the 82-inch at McDonald?”

[Edmondson]: “So we started paying, what was it, $600 a year for 15 nights — it’s a lot more expensive than that now!”

As the interviewer points out, this collaborative effort was “the kernel of what we may now call the National Observatory.”

At the time of the interview (1977), Indiana University was still purchasing time at McDonald. These days, IU works jointly with Wisconsin and Yale at the WIYN 3.5m Observatory on Kitt Peak, but I notice that an astronomer from Texas Christian University is using the 2.1m Otto Struve Telescope at McDonald to study open clusters from the WIYN Open Cluster Study. Astronomy—still a team sport.

So, this is a very long introduction to the book I’ve been reading this week, Big and Bright: A History of the McDonald Observatory by David S. Evans and J. Derral Mulholland (1986). It’s interesting enough on its own, as a history book, but this copy is made even more so by the inscription inside the front cover and a letter that was left tucked inside:

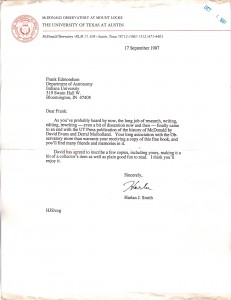

The inscription reads: “For Frank Edmondson with many thanks for your help and hoping we got it right—David S. Evans—8th September 1987”

You can click on the image to see a full-size image of the letter. It reads as follows: “Dear Frank: As you’ve probably heard by now, the long job of researching, writing, editing, rewriting—even a bit of dissention [sic] now and then—finally came to an end with the UT Press publication of the history of McDonald by David Evans and Derral Mulholland. Your long association with the Observatory more than warrants your receiving a copy of this fine book, and you’ll find many friends and memories in it. David has agreed to inscribe a few copies, including yours, making it a bit of collector’s item as well as plain good fun to read. I think you’ll enjoy it. Sincerely, Harlan J. Smith.”

I hope Prof. Edmondson enjoyed the read. I know I will.