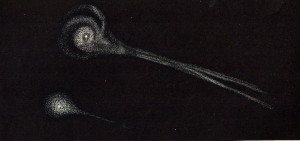

Comet Biela, February 1846. From E. Weiß: “Bilderatlas der Sternenwelt”, 1888.

One of the challenges of working on the history of science is that I’m constantly having to forget things that I only just memorized or figured out. This need to learn/un-learn has been particularly acute since my arrival in Bangalore. I’ve been buried in the ephemera of the founding days of astrophysics—correspondence, observational data, eclipse photographs, equipment—and on Wednesday, I’ll be going up to Kodaikanal Observatory to study the historical instruments in situ. I’ve spent a lot of time puzzling through C. Michie Smith’s thoughts on the D line in the solar spectrum, and reading along as John Evershed’s thoughts on sunspots evolved over the course of a few decades.

It’s fascinating, watching a scientific argument grow, falter, and grow again.

The Indian Institute pf Astrophysics has a small collection of Evershed’s letters to and from William Huggins, F.R.S. Although friendly, the two men (and presumably Margaret Huggins and Mary Evershed, who remain in the background as “wives” even though they had a great deal to do with the science successes of both men) were quite cagey in their correspondence. They shared data and floated ideas without ever committing to a particular theory or revealing everything they knew. Reading the letters against their published papers shows that both astronomers left out more than than they included in their personal discussions; Evershed saw Huggins as a competitor as much as a mentor and friend.

Interesting stuff. But what I’ve really had to focus on this past couple of weeks, as I dig more deeply into the history of solar physics, is the art of comprehension without retention. That is, I need to understand Evershed’s early theories, but also need to forget about them as they were eventually proved incorrect. For example, yesterday I found myself drawing a line through my notes on Hervé Faye’s claim that the sunspots were caused by an upflow of material too hot to radiate properly, just to remind myself that later Evershed demonstrated that the upflow was cooler than the surrounding area. Sometimes I can see a problem with a theory based on my own knowledge; sometimes I have to wait until I’ve read three more Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society before I realize I need to forget a few more things.

The first article I picked up this morning started this cycle up again.

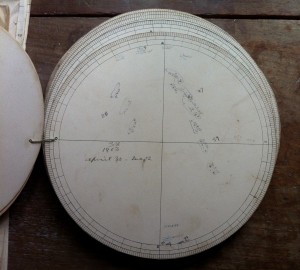

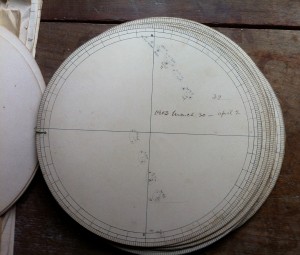

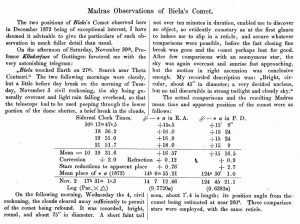

I’ve been looking at Norman Pogson’s original observation logs and comparing them with his published papers and catalogues. This morning, I found an interesting notice of his observations of Comet Biela in December 1872 (click on the image to download the entire notice):

Norman R. Pogson, “Madras Observations of Biela’s Comet,” Astronomische Nachrichten, Vol. 84, (August 1874), pp. 183 – 186.

Kind of cool. But a quick Internet search tells me that Comet Biela was last sighted in 1852—fourteen years before Pogson’s viewing. I know Pogson was an under-appreciated astronomer, but is it possible we’ve completely forgotten about his observations?

As it turns out, Pogson’s claim that he had spotted Biela was challenged as early as January 1873. Pogson may have been misled in his identification by another astronomer, Klinkerfues, who told him to search for Biela near Theta Centauri. Or he may have been encouraged to identify the moving object as Biela since it was roughly coincident with what would later be identified as a Bielan meteor shower, created by the comet’s disintegration. However the confusion arose, by 1892, it was accepted fully that Pogson’s comet, now known as X 1872 X1, was not Biela at all, but some other object in motion. Pogson was able to record only two locations for his comet, so it is impossible to determine X 1872 X1’s orbit or period. Today, we may know X 1872 X1 by a second name, or Pogson may have made the comet’s only sighting before it broke up like Biela.

W. H. S. Monck, “Pogson’s Comet and the Bielan Meteors,” Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, Vol. 4, No. 21 (1892), p.19.

So, this morning, I learned that Norman Pogson observed Comet Biela from the Madras Observatory in December 1872. Approximately ten minutes later, I began the process of unlearning this bit of information and replacing it with conclusions drawn in the last two decades of the nineteenth century. After lunch, I may need to unlearn those bits as well and absorb instead analyses of X 1872 X made in the twentieth—or even better—twenty-first century.