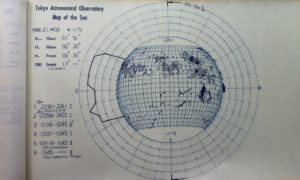

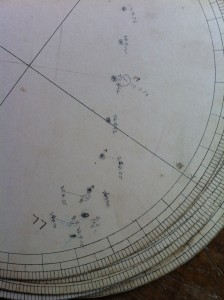

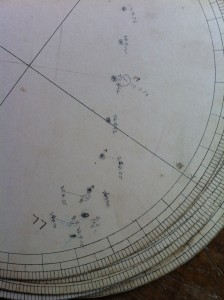

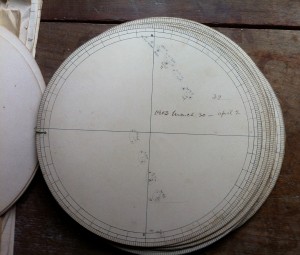

Sunspot observation record, April 30-May 1, 1903. Image courtesy of Indian Institute of Astrophysics/JR

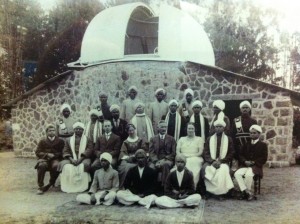

I was fortunate enough to spend some time studying the historic instruments and library collection at Kodaikanal Observatory in Tamil Nadu this past week. Run by the Indian Institute of Astrophysics, the observatory was founded in 1899 to facilitate solar observing. In 1907, John Evershed arrived on the scene to (quite famously) bring his “auto-collimating spectroheliograph” online. You can imagine my excitement when Mr. Selvendran, Senior In-Charge at KO, opened the door to the spectroheliograph room and slid open the shed roof to expose the instrument’s mirror. So cool.

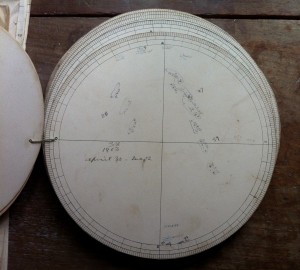

But I’m getting ahead of myself. I spent my first day poking around KO’s fascinating library. Journals, books, catalogues, and ephemera stacked literally from floor to ceiling. So much stuff that I scarcely knew where to begin. But when I saw a stack of paper circles tucked into a corner shelf, I knew how I would spend the afternoon. I had only just read about these circles in one of C. Michie Smith’s (KO’s first director) annual reports.

Excerpt from Kodaikanal and Madras Observatories report for the year 1904.

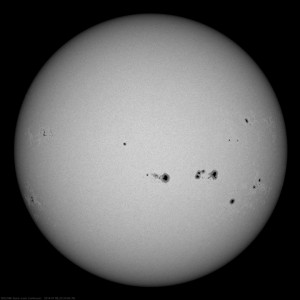

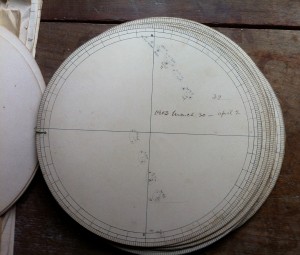

Each of these 8-inch paper discs contains a record of 3-7 days of sunspot observations. Each spot was marked in pencil and assigned a letter (A, B, etc.). Every day, the observer recorded the new position and appearance of the lettered spots as they traversed the solar “surface”, i.e., the photosphere. For instance, in the following plates, sunspots A and B are shown moving from NNE to W between March 18 and 29, 1903.

Sunspot Observations, March 18-29, 1903. Image courtesy Indian Institute of Astrophysics/JR.

Sunspot Observations, March 18-29, 1903, detail. Image courtesy Indian Institute of Astrophysics/JR.

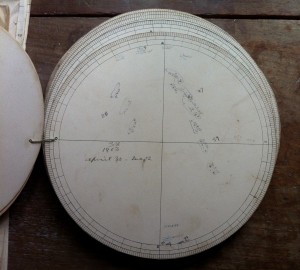

The next image shows that those same spots continued westward between March 30 and April 2, 1903, breaking up as they went. You can also see a second line of spots traveling roughly parallel to the solar equator. They started out as indistinct patches at the eastern edge of the disc on the March 27-28. The March 30-April 2 disc shows how long it took for them to move half way across the Sun.

Sunspot Observations, March 30-April 2, 1903. Image courtesy Indian Institute of Astrophysics/JR.

According to C. Michie Smith, observers hand-recorded sunspots on 343 out of 365 days in 1904. What dedication, and this at a time when they didn’t really know what sunspots were. Observers just put in the hours and trusted that their efforts would one day lead to enlightenment.