I just spent several hours watching Patricio Guzmán’s Nostalgia for the Light. It’s a 90-minute film and a more focused audience could probably have knocked the viewing out in one sitting. I, on the other hand, found myself completely distracted by the telescope porn in some scenes, and watched them two or three times. When combined with several Internet research forays, I at least doubled, if not trebled, my viewing time.

If you’ve seen the trailer for the movie, you already know that it is a visually spectacular film. If you haven’t seen the trailer, take a moment:

Obviously, I picked up the film for the observatories, but they were used mostly as a heuristic device, framing the director’s meditation on the aftermath of Chile’s Pinochet era. Guzmán contextualizes the terrors perpetrated under Pinochet and Chilean society’s subsequent refusal to own up to them in universal natural history (i.e., what emanates from the Big Bang), but Nostalgia is really about the human, not the eternal, epoch. And for all the work the director did to draw parallels between astronomy, archaeology, and the quest to unearth (literally) the remains of Pinochet’s victims, the film is almost exclusively about our understanding of the immediate past. The trauma of nostalgia in Guzmán’s narrative requires memory and suppression, or the development of historical consciousness. The universe does not remember, the universe does not forget. Yes, we can trace the calcium in our bones to its origin in the stars, but that “biological memory” has no moral drive behind it. The bones don’t hold the universe accountable for the calcium, while the survivors of Pinochet’s political massacres do hold the murderers so.

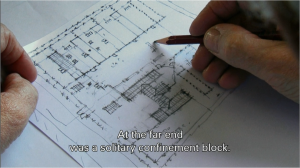

Unless. I was struck by the scenes focused on the work of architect Miguel Lawner. Lawner mapped Pinochet’s prisons by turning his body into a measuring device, moving it through space, step by step, until it remembered dimensions, locations, and functions of everything around it. It’s difficult to gauge how much of his mapping ability came from conscious effort and how much could be attributed to what we like to call “muscle memory.” Either way, it raises questions about the role of the body—beyond the brain—in preserving memories.

Structurally, this movie reminded me quite a bit of Herzog’s Cave of Forgotten Dreams. Like Herzog, Guzmán worked to tie together archaeology, historical consciousness, the human present, and vision. But Cave was much more optimistic about the human condition. Nostalgia reminds us that moving out of the cave doesn’t guarantee civilization, or if it does, it’s a civilization shot through with darkness.