Wheels down at Dulles International, OV-103 (Discovery), April 17, 2012. Image Credit: NASA

The Internet can be an amazing place, or an amazing tool, however you want to conceptualize it. Yesterday, instead of working on an article I really need to finish, I spent two hours watching the transfer of the Space Shuttle Discovery from Kennedy Space Center to Dulles International Airport, courtesy of NASA TV. During the two hours I was glued to NASA’s live stream, I serial tweeted, carried on several fragmented but enthusiastic online conversations about the landing, updated my fb status, took dozens of screenshots just for the hell of it, and did some preliminary research on the terminal at Dulles. I eventually connected with my partner via cellphone, and we watched the landing together (along with one or two of her co-workers who wandered into her office during our phone call).

NASA 905 SCA (Pluto 95 Heavy) & OV-103 flyover Washington, D.C., April 17, 2012. Image Credit: NASA

Boy, I burned through a lot of nervous energy yesterday, worrying that something would go wrong. It’s a good thing launch control had their emotions under control, if only because they had to land the T-38 escort (Pluto 98) in a fuel critical situation. While it’s not particularly unusual for me to grow sentimental when engaging with space science, it is atypical of me to confess to those sentiments to everyone following me on twitter. Unquestionably, the Shuttle program has shaped the course of my life and, to be honest, that hasn’t always been a good thing. So, while part of me was sad yesterday as Discovery disappeared behind the terminal at Dulles, a greater part of me was relieved to see it all finally come to an end.

If you follow me on twitter, you might have seen my serial tweets as the SCA taxied to the terminal. If you’re my facebook friend, you probably saw the conversation about wood-fired propulsion systems. If you’re one of my architecture students, you’d better have been in class this morning to see me use the following image as a transition between Frank Lloyd Wright and Louis Kahn.

Passenger Terminal, Dulles International Airport. Image Credit: NASA

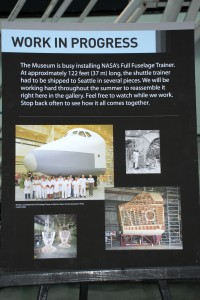

That’s Eero Saarinen & Associate’s passenger terminal (1958-62) in the background. As as I said in class today—this was one of the first American airports built specifically for jet traffic. It’s a gateway to the deeply symbolic political landscape of the nation’s capital. But it’s not just a gateway, it’s a Modern gateway, in terms of program, structure, and function. The caternary curve of the cable-reinforced concrete roof simultaneously implies the rest and motion experienced by the world traveler. The splay of the massive columns that anchor the steel cables on either side of the terminal provides both formal and structural tension. Passenger circulation paths are controlled through the use of “mobile lounges.” That they function as spaces of surveillance is all but masked by their efficient use as people movers.

Saarinen’s design marks the moment the federal government committed itself to international air travel. Discovery’s retirement to the Smithsonian’s Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in Chantilly marks the moment the government decided to stop investing in space exploration, the logical outcome of all that travel through the atmosphere in 747s. More importantly, yesterday’s landing marked the end of (one version of) the Modernist project, the progressive, curious, optimistic one that put us into rapid motion at mid-century. If we’ve given up on looking at the universe around us, and it seems we have, I’m afraid we’ve pretty much given up on humanity.