This week’s selection features Leiden Observatory, the oldest university observatory in the world. The observatory was established in the Academy Building of the Leiden University on Rapenburg Gracht (Canal) in 1633. The “new” observatory (the two domes at the left), now called the Old Observatory, was built next to the Witte Singel (White Canal) in 1860. The photo above was taken from the Witte Singel/Zoeterwoudsesingel bridge a year ago, on December 21, 2010, to mark the shortest day of the year in the Northern Hemisphere. Happy Winter Solstice!

Wallpaper Wednesday

21 12 2011Comments : Comments Off on Wallpaper Wednesday

Categories : Observatories, Wallpaper

Astronomy Korea

19 12 2011

14 meter millimeter-wave radio telescope at the Taeduk Radio Astronomy Observatory. Photo courtesy Korea Astronomy Observatory.

A long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away, I was a contributing editor to a Korean-American cultural magazine. I’ve been meaning to dust off my language skills to do some research on the current state of observatories in South Korea, but every time I get started, I’m put off by how frequently academic and popular articles focus on Cheomsongdae observatory, built in 632-647 CE, rather than on contemporary developments. I suppose there’s nothing inherently wrong with that, but it seems a bit Orientalist to me, implying astronomy in Korea somehow stopped progressing during the Silla Dynasty period.

When my twitter feed lit up last night with news of Kim Jong-il’s demise, I began contemplating the state of astronomy in Korea again. It’s true the discipline went through some tough times during the twentieth century. For instance, during the Japanese occupation (1905-1945), Koreans weren’t allowed to be astronomers.[1] Obviously, there’s not much I can say about astronomy in North Korea following the conclusion of WWII, other than it must be amazing to look up at the night sky there, since there’s so little light pollution. In South Korea, astronomy as an academic field was slow to grow. The first bachelor of science program was founded in 1958 at Seoul National University; the second began about ten years later at Yongsei University. The Korean Astronomical Society was founded in 1965 and joined the International Astronomical Union (IAU) in 1973.[2] The Korea Astronomy and Space Science Institute (KASI), the national astronomy research institute of South Korea, was established in 1974.

I mention KASI for a reason. Although there are now other institutions and professional astronomical organizations in South Korea, KASI in particular turns the popular conception of Korean astronomy as an “ancient science” on its head. The research initiatives at KASI are numerous and diverse. KASI-supported observations started in 1978 with a 61-cm reflecting telescope at the Sobaeksan Optical Astronomy Observatory (SOAO). From there, it expanded into radio astronomy, founding the Taeduk Radio Astronomy Observatory (TRAO) in 1985. TRAO continues to operate with a 14 meter millimeter-wave radio telescope. In 1996, Bohyunsan Optical Astronomy Observatory (BOAO) was opened with the largest optical telescope in the country and in 2009, South Korea moved to join the Giant Magellan Telescope initiative.

KASI opened the 21st century with one of my favorite projects, the Korean VLBI Network KVN Group. Return visitors to this site may remember my obsession with the NRAO Very Long Baseline Array. A comparable scheme, KVN is the first Very Long Baseline Interferometer facility in Korea, consisting of three 21 meter radio telescopes, erected in Seoul-Yonsei University, Ulsan-Ulsan University, and Jeju-Tamna University. The maximum baseline length of the KVN is considerably shorter than that of the VLBA (compare 5,000 miles with the 480 km line between Seoul and Jeju).[3] However, KVN can be used in conjunction with Japanese and Chinese VLBI networks to form the East Asian VLBI network (EAVN), which is expected to be comparable to the VLBA in spatial resolution, sensitivity, and imaging fidelity.

This post really doesn’t have much to do with North Korea, does it? It’s wrong to envy their dark skies, I know, but it would be nice to have a decent view of the Milky Way for a change.

—————-

[1] I. S. Nha, “Astronomy in Korea,” The Third Pacific Rim Conference on Recent Development on Binary Star Research. Proceedings of a conference sponsored by Chiang Mai University, Thai Astronomical Society and the University of Nebraska-Lincoln held in Chiang Mai, Thailand, 26 October -1 November 1995. ASP Conference Series, Vol. 130, 1997, ed. Kam-Ching Leung, p. 313.

[2] Ibid., 313. North Korea joined the IAU separately in 1961 (see proceedings from the IAU XIth General Assembly, Berkeley, 1961). For the record, the IAU reported that North Korea “may be opening up to the rest of the world” in the 2008 Informational Bulletin no. 102 (see p. 75).

[3] Kiyoaki Wajima, Hyun-Goo Kim, Seog-Tae Han, Duk-Gyoo Roh, Do-Heung Je, Se-Jin Oh, Seog-Oh Wi, and Korean VLBI Network Group, “Korean VLBI Network: the First Dedicated Mm-Wavelength VLBI Network in East Asia,” XXVIIIth General Assembly, International Union of Radio Science (URSI), New Delhi, October 2005.

Comments : Comments Off on Astronomy Korea

Categories : Observatories

Wallpaper Wednesday

14 12 2011Kennedy Space Center’s Launch Complex 39 includes two pads, A & B. Although today they’re associated most frequently with the Space Shuttle program, they were designed originally for the massive Saturn V rockets used during the Apollo program. On November 9, 1967, Apollo 4 became the first rocket to launch from LC-39A. A total of twelve Saturn V rockets were sent up from that pad. In contrast, LC-39B saw only one Saturn V, the one used to launch Apollo 10 on May 18, 1969. The Apollo 10 mission was a test drive of sorts, the last test mission before NASA made the final leap to the moon with Apollo 11.

Today’s wallpaper marks the launch of Apollo 11 on July 16, 1969. As with most big news events, everyone has a story to tell about the launch and lunar landing. My story is quite short, as I was only two years old at the time. I remember my father reaching out from where he was sitting in front of the television, lifting me onto his lap, and saying, “Watch this, Susie, this is important.” There are many other things he did and said that affected the way I live(d) my life, but I suspect that one moment determined more than either of us could have guessed at the time (especially me—what does a toddler know?).

Comments : Comments Off on Wallpaper Wednesday

Categories : Observatories

Wallpaper Wednesday

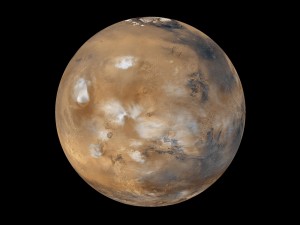

23 11 2011Today’s wallpaper image is probably an obvious choice.[1] We arrived in Florida yesterday for the Mars Science Laboratory launch, still scheduled for this Saturday. We spent today sorting out our credentials (two separate trips to Kennedy Space Center Visitor Complex) and walking on the beach (two separate trips to Cocoa Beach). Tomorrow, we’re going back to KSCVC for the day (lunch with an astronaut, ice skating in the Rocket Garden?). Official NASATweetup events start at Kennedy Space Center Friday morning and run until 6:00 in the evening. There’s a lot on the agenda, including a tour of the Vehicle Assembly Building, so hopefully I’ll have some up-close-and-personal photos on my flickr site next week. If the launch goes as scheduled, I’ll be arriving at the NASATweetup viewing area sometime before 6:45 a.m. Wish me luck with that.

This seems like a good time to make a confession: I don’t actually care about Curiosity’s official mission. The search for environments capable of sustaining life—in the past or future—isn’t what drives my interest in planetary exploration. I’m much more intrigued by the details of geological processes: what are the specificities of volcanic activity on Mars? How has Mars’ environment changed the nature of sedimentary rock formation? It would be interesting if there was (carbon based?) life on Mars at some point in the past, but “is there life out there?” doesn’t even make my top one hundred list of Questions To Which I Want To Know The Answer.

Click on the linked image to download the photo of Mars. It’s not quite wallpaper proportions, but if you fill in the rest of your desktop with a solid black background, it will look sweet!

[1] As an aside, every time I look at this image, I remember the night I made the mistake of studying Mars through our Meade DS-10 telescope. The retinal burn was tremendous; I saw an after-image of the planet with the polar ice cap for days afterward.

Comments : Comments Off on Wallpaper Wednesday

Categories : Observatories

Wallpaper Wednesday

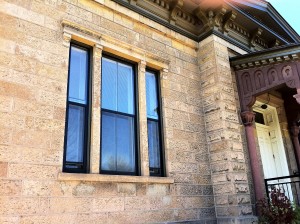

9 11 2011Today’s wallpaper features McCormick Observatory, located on Mt. Jefferson on the campus of the University of Virginia. The observatory is named after Leander J. McCormick, donor of the 26-inch astrometric refractor still housed under the dome of the building. Usually we see the names Warner & Swasey associated with the instruments (they designed the telescopes for the Kirkwood, Lick, University of Illinois, Theodor Jacobsen, and Yerkes Observatories, amongst others), but at University of Virginia, they were charged with the design of the original observatory dome, a first for the duo.[1] The dome was manually operated, but the track system provided for such an ease of motion that Warner & Swasey immediately applied for a patent for their design.[2] Construction work began in 1882; the observatory was formally dedicated on April 13, 1885.

In addition to the dome room, the original building included a wing that housed the calculating rooms and a bedroom. If you looked at the image above and thought that the building’s detailing looked more suited to a cathedral than an observatory, you would be right: the Medieval Renaissance windows and buttresses echo a similar motif used (more appropriately) on the University chapel.[3] The director’s house (now known as Alden House, or Observatory House #1) was also built in 1882, with additional funds supplied by McCormick.

To download wallpaper (standard sizes) of the above image, click here.

————————

[1] Paul B. Barringer, James M. Garnett, and Rosewell Page, Eds., University of Virginia: Its History, Influence, Equipment and Characteristics (New York: Lewis Publishing Company, 1904): 9.

[2] After searching the patent registry, I can only guess that they were trying to protect their design for the process of cutting teeth of gear wheels, Patent No. 333, 488.

[2] Richard Guy Wilson and Sarah A. Butler, University of Virginia: The Campus Guide (Princeton: Princeton Architectural Press, 1999): 144.

Comments : Comments Off on Wallpaper Wednesday

Categories : Observatories, Wallpaper, Warner and Swasey

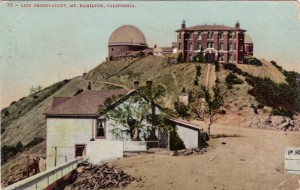

Lick Observatory

8 11 2011Click on the images for high-resolution scans. For earlier posts detailing Lick Observatory, see here.

Comments : Comments Off on Lick Observatory

Categories : Ephemera, Observatories

Wallpaper Wednesday

26 10 2011

IceCube Neutrino Collector at the Admundsen-Scott South Pole Station. Image credit: National Science Foundation/Keith Vanderlinde

Are you wondering what the astronomers at University of Wisconsin are up to these days? Long gone are the days of optical astronomy with a refracting telescope. Today’s research problem is the search for the neutrino and University of Wisconsin is right on it. The above image is a silhouette of the IceCube South Pole Neutrino Collector, a neutrino telescope managed by a collaboration of 36 institutions, including the University of Wisconsin and the National Science Foundation.

Click on the image to see more South Pole and IceCube images, or look here for “IceCube Explained.”

Comments : Comments Off on Wallpaper Wednesday

Categories : Observatories, Wallpaper

Washburn Observatory

26 10 2011I was in Madison, Wisconsin, for a conference last week. I took advantage of the beautiful autumn weather to pay a quick afternoon visit to the Washburn Observatory on the University of Wisconsin campus. The observatory stands on top of Observatory Hill, at a point from which visitors have a fantastic view of Lake Mendota. Unfortunately, I only had my iPhone camera with me, so I couldn’t do the building justice in terms architectural documentation (and didn’t even try to make an appointment to view the instruments inside, where I was sure my camera would disappoint me), but did manage to capture a few interesting exterior details.

The observatory exists because of the generosity of former Wisconsin governor Cadwallader C. Washburn, who donated the money and selected the site for the building. Washburn was apparently motivated by a desire to show up those hotshots at Harvard College Observatory—he agreed to fund the project, but required that the instrument to be acquired for the observatory be larger than the 15″ refractor then in use at Harvard. Work on the observatory began in May 1878 under the supervision of architect David R. Jones (also selected by Washburn), and Alvan Clark and Sons built a 15.6″ refractor for the new observatory, temporarily putting Harvard in its place.[1]

What stands now on Observatory Hill bears a close resemblance to the original observatory. Even before the formal dedication in 1882, the building had been expanded beyond the original program, which had called only for a domed space for the telescope, with two flanking wings to house a meridian circle and other equipment.

The first director of the observatory, James Craig Watson, requested that calculating rooms and living quarters be added; the addition, built to the east and connected to the first building by a short passageway, was completed in 1881. Watson also provided funds for a second observatory, intending to train students with the telescope in that space rather than with the refractor under the main dome.

In one of those tragic twists of fate, both Washburn and Watson died before the observatory’s dedication (Washburn in 1882 , Watson in 1880). Edward S. Holden (b. 1846-d. 1914) transferred from the U.S. Naval Observatory to Wisconsin, where he served as director of the observatory from 1881-1885.[2] By the end of Holden’s tenure, the observatory’s architecture was largely set in place; only a few small changes took place over the next 50 years or so. For instance, the porch on the east wing was enclosed in the 1920s.

A wrought-iron balcony was added to the main dome (only accessible from the telescope room) at some later date, and the interior of the building was reconfigured at various times to accommodate changing needs for office and classroom space.

”] Like most observatories of its age, its instrumentation is useful for lessons in the history of astronomy and public outreach. The real astronomical research at University of Wisconsin has moved on to other spaces and other pursuits. The building was completely renovated in 2008-09 so that it could be given over to the UW College of Letters and Sciences Honors Program. Public viewing sessions with the 15.6″ refractor are still held every other Wednesday (or so); otherwise, anyone is free to walk around and enjoy the observatory’s exterior at any time of the day.

Like most observatories of its age, its instrumentation is useful for lessons in the history of astronomy and public outreach. The real astronomical research at University of Wisconsin has moved on to other spaces and other pursuits. The building was completely renovated in 2008-09 so that it could be given over to the UW College of Letters and Sciences Honors Program. Public viewing sessions with the 15.6″ refractor are still held every other Wednesday (or so); otherwise, anyone is free to walk around and enjoy the observatory’s exterior at any time of the day.

______________

[1] This post relies upon information included in the the Feasibility Study for Washburn Observatory conducted by Isthmus Architecture, Inc. in April 2004.

[2] Holden left Wisconsin in 1885 to become the president of the University of California. In 1888, he became the first director of Lick Observatory.

Comments : Comments Off on Washburn Observatory

Categories : Alvan Clark & Sons, Observatories

A. I. Eremeeva (А. И. Еремеева)

18 10 2011So, yes, I’m in the process of slowly acquiring the remainder of Frank K. Edmondson’s library, or at least the parts of that library that are relevant to my work in the history of astronomy and instruments. Many of the books are dated, of course, but still serve as good reminders of the extensive intellectual network required to support a global discipline like astronomy. Really, all you need is the name of a single individual working as an institutional astronomer or academic—an observatory, a university—and you have an entry point into the entire history of astronomy, not just in the United States, but in the world.

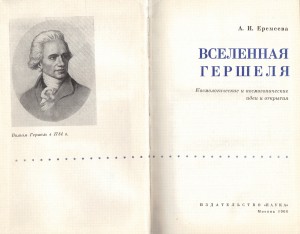

The most recent bit of proof of this assertion is Prof. Edmondson’s copy of A. I. Eremeeva’s Herschel’s Universe: Cosmological and Cosmogonic Ideas and Discoveries [Вселенная Гершеля: космологические и космогонические идеи и открытия] (Moscow: Science [Наук] Press, 1966). Inside the front cover of the book is a short, handwritten note from the author:

Reading between the (few) lines, it would appear that Drs. Eremeeva and Edmondson met in Washington, D.C., sometime after the breakup of the Soviet Union. As a token of collegiality and possibly friendship, Dr. Eremeeva offered a copy of what must have been her first book, probably based on her doctoral work.[1]

Title page from A. I. Eremeeva, Herschel's Universe: Cosmological and Cosmogonic Ideas and Discoveries, 1966

It took a little more work than this kind of thing usually does, but I finally tracked down a few other examples of Dr. Eremeeva’s historical research. Most of it seems akin to what I’m doing here, although much more professional and thoroughly researched: writing the history of astronomy through a series of biographical essays. Her publications cover a long list of astronomers and their discoveries, many not well known to the average American (thanks, Cold War). It seems that many of her subjects had ties to Pulkovo Astronomical Observatory outside Saint Petersburg.[2] I’ve appended to the end of this post a few examples of her essays. One of them is English, so there’s something for everyone, particularly if everyone is in the mood to read about political purges of scientific communities. I should stress, this is only a partial list. If you run “Eremeeva, A. I.” or “Eremeeva, Alina Iosifovna” through the search query at the SAO/NASA Astrophysics Database, you’ll get at least 61 hits related to her work.

I haven’t been able to figure out Dr. Eremeeva’s precise connection to Pulkovo Astronomical Observatory. It’s her research interest, certainly, but her institutional affiliations all seem to be associated with Moscow, so I’m not sure how she connects up with the history of the St. Petersburg institution. I mention this because tucked inside the book she gave Prof. Edmondson was a souvenir card from Pulkovo.

Clearly, I have more research to do. Look for another post on the topic one day soon.

————————————

Works by A. I. Eremeeva, Ph.D. in Physics and Mathematics, Shternberg State Astronomical Institute, Moscow (А. И. Еремеева, кандидат физико-математических наук, Государственный астрономический институт им. П.К. Штернберга, Москва), listed in chronological order:

[Russian] “The Life and Work of Boris Petrovich Gerasimovich, on his 100th Birthday.” In Historical and Astronomical Research (Историко-астрономические исследования), Vol. 21 (1989): 253-301.

[English] “Political Repression and Personality: The History of Political Repression Against Soviet Astronomers.” Journal for the History of Astronomy. Vol. 26 (1995): 297-324.

[Russian] Astronomy at the Turn of the Twentieth Century. Pulkovo-Dubna: Phoenix Publishing Center, 1997.

[Russian] “Meteors, ‘Thunder Stones’ and the Paris Academy of Sciences before ‘The Court of History.’” Nature, No. 8 (2000).

[Russian] “Pioneer of National Physics, on the 150th birthday of academician A. A. Belopol’sky.” Bulletin of the Russian Academy of Sciences. Vol. 74, No. 6 (2004): 534-543.

[Russian] “175 years of the State Astronomical Institute of P. K. Shternberg, Moscow.” Nature, N0. 10 (2006).

[Russian] “The Troubled Genius of Ernst Chladni.” Nature, N0. 12 (2006).

[Russian] Giovanni Schiaparelli (1835-1910), On the his 175th Birthday and 100th Anniversary of his Death. Astronet (online) (2010).

—————-

[1] This assumption might not be true, since she published a second book that same year, Outstanding Astronomers of the World [Выдающиеся астрономы мира], also with Science Press. These are the earliest volumes I could find, so possibly both grew from her doctoral work.

[2] Did you know that at one time, Pulkovo had the largest refracting telescope (30″) in the world? It was built by Alvan Clark & Sons, who also built the telescope at Lick Observatory that displaced Pulkovo as “world’s largest” in the 1880s.

Comments : Comments Off on A. I. Eremeeva (А. И. Еремеева)

Categories : Observatories

Wallpaper Wednesday

12 10 2011

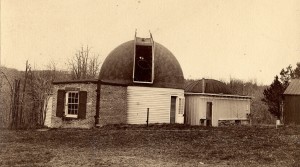

Henry Draper's Astronomical Observatory, c. 1880. Photo courtesy of the Hastings Historical Society.

This week’s wallpaper offers you a glimpse at the site of some significant astronomical accomplishments, Henry Draper’s observatory in Hastings-on-Hudson, New York. Henry Draper was an astronomer, but more importantly, he was an astrophotographer. He is credited with taking the first photograph of a star’s spectrum in 1872 (Vega, in the constellation Lyra). He took the first known photo of the Orion Nebula in 1880, and the first wide-angle photo of a comet’s tail in 1881 (Tebbutt’s Comet).

Draper’s observatory was built on his family’s property in the spring of 1860.[1] Before building the observatory, he had spent a number of years trying, and failing, to grind a series of 15-1/2″ mirrors. In 1860, his father, the Doctor John Draper, traveled to Europe, where he consulted with John Herschel on the best process for mirror-silvering. Dr. Draper sent Herschel’s advice back to his son, who apparently put it to good use in finishing his reflecting telescope, which he then set up in his new observatory. The observatory was 17-1/2 feet square, two stories tall, and excavated out of solid granite on four sides (the side facing east was open). In 1862, he added a 9’x12′ photo lab to the south side of the building.

In the winter of 1862, Draper took a series of solar images on daguerrotypes and tannin plates. In April of the same year, he recorded multiple images of the moon on dry plates, varying the lengths of the exposure time. He repeated this activity in August 1863, producing perhaps the most significant set of lunar images in the history of astrophotography (1500 exposures in all).

In 1867, Draper began polishing a mirror for an even larger telescope, and in 1869, built a new, larger dome on the observatory to accommodate it. The telescope took multiple forms over the course of its life: sometimes with a front-view (Herschelian) and sometimes a Newtonian mount; by 1874, it had been changed over to a Cassegrain. Draper used this larger instrument to capture the first spectrum of a star (May 1872). He took a break from stellar spectrum photography in 1874 to participate in the expedition to view the transit of Venus (for which he earned a Congressional medal), but autumn of that year found him focused on Vega again with an experimental instrument he called a “spectrograph.” He continued to push against the limits of technology, producing not just photographs of the Orion nebula (a fifty-minute exposure!) and the tail of Tebbutt’s Comet, but the spectrum of Jupiter as well.

Unfortunately, Draper died relatively young, at the age of forty-five. There’s no telling what else he could have accomplished as an astrophotographer had he lived a decade or two longer. After his death, his widow decided to fund Edward Pickering’s photographic spectrography at the Harvard College Observatory. The end result of this money-research collaboration was the Draper Catalogue of Stellar Spectra (1890). Over the next two decades, Annie Jump Cannon expanded the catalogue with her own research, turning it into a rather large treatise that was published across nine volumes of the Annals of the Harvard College Observatory. Cannon’s work eventually led to the development of the Harvard spectral classification scheme (O, B, A, F, G, K, M) that is still in use today.

[1] George F. Barker, Memoir of Henry Draper, 1832-1882. Read before the Academy, April 18, 1888 (yes, really).

Comments : 2 Comments »

Categories : Observatories, Wallpaper