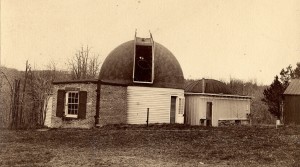

Henry Draper's Astronomical Observatory, c. 1880. Photo courtesy of the Hastings Historical Society.

This week’s wallpaper offers you a glimpse at the site of some significant astronomical accomplishments, Henry Draper’s observatory in Hastings-on-Hudson, New York. Henry Draper was an astronomer, but more importantly, he was an astrophotographer. He is credited with taking the first photograph of a star’s spectrum in 1872 (Vega, in the constellation Lyra). He took the first known photo of the Orion Nebula in 1880, and the first wide-angle photo of a comet’s tail in 1881 (Tebbutt’s Comet).

Draper’s observatory was built on his family’s property in the spring of 1860.[1] Before building the observatory, he had spent a number of years trying, and failing, to grind a series of 15-1/2″ mirrors. In 1860, his father, the Doctor John Draper, traveled to Europe, where he consulted with John Herschel on the best process for mirror-silvering. Dr. Draper sent Herschel’s advice back to his son, who apparently put it to good use in finishing his reflecting telescope, which he then set up in his new observatory. The observatory was 17-1/2 feet square, two stories tall, and excavated out of solid granite on four sides (the side facing east was open). In 1862, he added a 9’x12′ photo lab to the south side of the building.

In the winter of 1862, Draper took a series of solar images on daguerrotypes and tannin plates. In April of the same year, he recorded multiple images of the moon on dry plates, varying the lengths of the exposure time. He repeated this activity in August 1863, producing perhaps the most significant set of lunar images in the history of astrophotography (1500 exposures in all).

In 1867, Draper began polishing a mirror for an even larger telescope, and in 1869, built a new, larger dome on the observatory to accommodate it. The telescope took multiple forms over the course of its life: sometimes with a front-view (Herschelian) and sometimes a Newtonian mount; by 1874, it had been changed over to a Cassegrain. Draper used this larger instrument to capture the first spectrum of a star (May 1872). He took a break from stellar spectrum photography in 1874 to participate in the expedition to view the transit of Venus (for which he earned a Congressional medal), but autumn of that year found him focused on Vega again with an experimental instrument he called a “spectrograph.” He continued to push against the limits of technology, producing not just photographs of the Orion nebula (a fifty-minute exposure!) and the tail of Tebbutt’s Comet, but the spectrum of Jupiter as well.

Unfortunately, Draper died relatively young, at the age of forty-five. There’s no telling what else he could have accomplished as an astrophotographer had he lived a decade or two longer. After his death, his widow decided to fund Edward Pickering’s photographic spectrography at the Harvard College Observatory. The end result of this money-research collaboration was the Draper Catalogue of Stellar Spectra (1890). Over the next two decades, Annie Jump Cannon expanded the catalogue with her own research, turning it into a rather large treatise that was published across nine volumes of the Annals of the Harvard College Observatory. Cannon’s work eventually led to the development of the Harvard spectral classification scheme (O, B, A, F, G, K, M) that is still in use today.

[1] George F. Barker, Memoir of Henry Draper, 1832-1882. Read before the Academy, April 18, 1888 (yes, really).

Interesting website. I enjoyed reading it.

“Draper’s observatory was built on his family’s property in the spring of 1960”

I think there’s a typo right………………………………………………………….here ^

Ah, thanks! Fixed it!