I’m moving offices, so I’ve been sorting through the stacks of paper that have failed to find a home in a file folder over the past two years. On top of my stack of archaeoastronomy articles was an analysis of the megalithic enclosures in the historical province of Alentejo in south-central Portugal.* I saved it because I thought it might be relevant to my dissertation (it wasn’t); I re-read it because I had been thinking about the distribution of megaliths across northern Europe while writing about Stonehenge knock-offs yesterday.

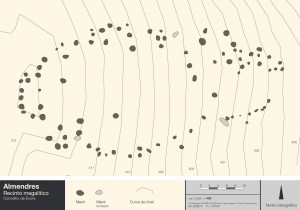

The Alentejo stretches south from the Tejo River to north of the Algarve (Faro District). The Évora district occupies the middle section of the Alentejo. Within the Évora district are twelve known stone enclosures built during the Middle Neolithic period (sixth to fifth millennia B.C.). Most of the enclosures were built in a horseshoe shape, with openings oriented to the east. The smallest complex, Vale d’el Rei, has twelve menhirs in a simple horseshoe shape; the largest, Almendres, has 94, with a more complicated configuration.

A new archaeological survey was conducted of the twelve known sites, including both the location of the extant menhirs and their relationship to the larger landscape (distance to horizon profile, horizon marks, maximum slope, axis of symmetry).** The survey demonstrated that eight of the twelve sites had axes with orientations within a range of 35.4° of azimuth, in approximately the eastern direction. The research team concluded that the probability of this common orientation occurring by chance was very low (~7 x 10^-7), and there could only be two explanations for it:

“either an astronomical target (Sun, Moon, or planets, based on the possible declinations for 6000-5000 B .C.) or a construction following the slope, turned to the direction of the far horizon, since we verified a Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient of .7 between the azimuth of the symmetry axis and the azimuth of the steepest slope.” (p.7)

I’m not sure of what I think of this first conclusion. What about the 1/3 of the sites that didn’t exhibit this commonality? And what about Xarez, which was excluded from the study because of controversial excavations (see **, below), but may have had a different configuration that then twelve sites included the study? At any rate, this initial conclusion motivated the research team to further analyze their data to determine which of the two options was most probable.

The data crunching is impressive and I direct you to the published article to read the description of their probability models (I am not qualified to comment on the validity of Bayesian analysis in this case). Ultimately, the team discarded the possibility that the structures had been positioned in regard to slope. That left them with option two—the stones were arranged in response to an astronomical target. But which target?

It’s possible that the stones had a lunar association—the crescent symbol is engraved on several menhirs in Almendres, Pórtela de Mogos, and Vale Maria do Meio. Most of the engraved surfaces face the east, which could indicate a lunar orientation. On the other hand, it could also indicate a solar orientation, much like that exhibited by the dolmens (stone tombs) in the same region. The builders of the monuments were likely hunters-gatherers-farmers and may have needed the stones as a tool for telling time or marking the seasons. Or maybe not. The authors seemed to hedge their bets, which is common when writing about ancient architectures, but didn’t leave me feeling convinced of their conclusions.

That being said, the tables that accompanied the article are quite valuable. They include menhir statistics (size, location, position, decorations), enclosure statistics (latitude, azimuth of steepest slope, slope, symmetry axis aximuth, declination, horizon altitude), elevation profiles and horizon features of the sites in the study, and site plans for the Almendres, Vale Maria do Meio, Portela de Mogos, Tojal, Cuncos, Sideral, Fontainhas, and Val d’el Rei enclosures. You can also see site plans for many of the enclosures, drawn by Pedro Alvin, at http://www.crookscape.org/sitios.html (scroll to the bottom of the page).

Notes:

*Fernando Pimenta, Luís Tirapicos, and Andrew Smith. “A Bayesian Approach to the Orientations of Central Alentejo Megalithic Enclosures.” Archaeoastronomy 22 (2009): 1-20.

**The archaeological survey did not include the stone circle of Xarez, citing controversial excavation and reconstruction techniques as described in: Manuel Calado, Menires do Alentejo central. Genese e evoluçâo da paisagem Megalitica regional, Lisboa. 2004. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation. University of Lisbon.