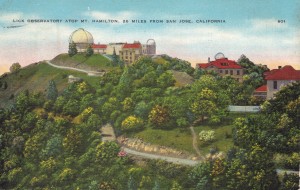

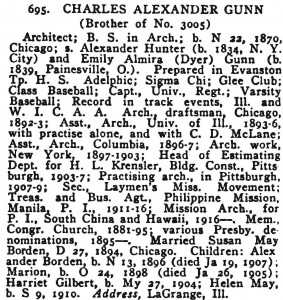

Knightridge Observatory, Bloomington, Indiana. Photo credit: JR.

In my earlier post about (then upcoming) events at the New Jersey Astronomical Association, I mentioned that the telescope at the Paul H. Robinson Observatory used a frame and mount acquired from Indiana University in the mid-1960s. The images of the frame in its previous home on the NJAA website inspired me to make the ten-minute trip over to Knightridge to inspect the abandoned IU observatory.

As you can see from the photo above, the rather squat building is now surrounded by a small, young wood in suburban Bloomington. At the time of its construction in 1936-37, however, this was a relatively remote site. In fact, it’s far enough outside the (then) city limits that I was surprised to see the obvious signs of electrical connections on the outside of the building (below). My neighborhood, which is closer to town, didn’t get electricity until 1960, so I guess I’m envious that IU managed to run a line out into the fields of Knightridge.

Approach from West, Knightridge Observatory. Photo credit: JR.

The building is in remarkably good condition. The mortar between the bricks is holding up well, and although the roof is highly oxidized, it’s still keeping the rain water outside where it belongs—for the most part, that is. The southeast roof of the building, including one of the shutter doors in the dome, was hit by a falling tree, unfortunately. If this hadn’t happened, the interior would still be dry and tight. Now, as you can see, not only are daylight and water making their way inside, so are plant seeds.

Storm Damage, Knightridge Observatory. Photo credit: JR.

From the outside, the dome looks truly round, but the construction details inside tell a different story. Underneath the sheet metal is a dome constructed of jointed wood ribs in-filled with flat lumber that diminished in length as it approached the apex of the dome. It’s not quite a corbeled beehive vault, but it gives a good approximation of the effect, rendered in wood.

Dome Interior, Knightridge Observatory. Photo credit: JR.

The dome was raised on steel tracks that rested on wheels attached directly to the brick walls of the observatory.

Wheel, Knightridge Observatory. Photo credit: JR.

All of the wires and most of the mechanics that supported the rotating dome have been stripped from the observatory, leaving behind interesting but non-functional bits and pieces on the second story of the building.

Abandoned Knightridge Observatory. Photo credit: JR.

Because the dome is no longer water tight, this upper floor is starting to rot. The rectangular opening that once held the mount for the telescope frame is dangerous territory, and I can only hope the people who’ve been using the observatory for late night séances are being very, very careful.

Second Floor, Knightridge Observatory. Photo credit: JR.

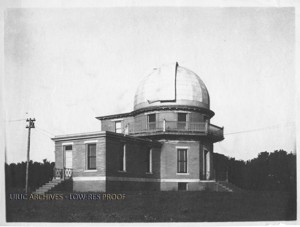

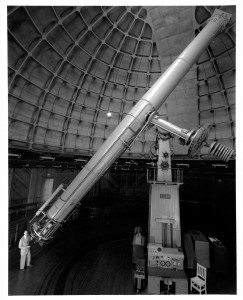

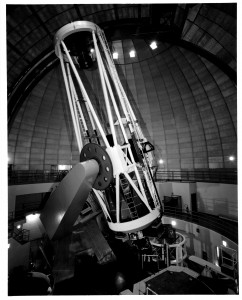

Despite the weather damage, it’s clear that this is one sturdy little building. It’s also clear that Professor Cogshall wasn’t all that concerned about aesthetics. Reconsider the Lick Observatory: a dome painted to resemble the heavens, walls finished in California redwood, floor finished with a high-polish mahogany. This modest university observatory bears no trace of a finish plaster or floor varnish. Cogshall was here to get the job done, apparently, and saw no need for embellishments that probably wouldn’t look like much under a red light at night, anyway.

You can view a few more photos of the abandoned building on my flickr site.