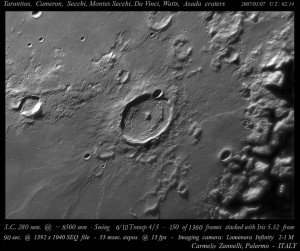

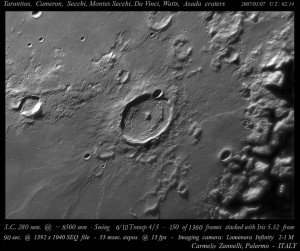

Taruntius Crater (with Cameron Crater). Image courtesy LPOD, December 3, 2008.

I wish I knew if this was a cautionary tale or a story of triumph.

Robert Curry Cameron, known to his friends and professors as Bob, matriculated at Indiana University in 1947. Circumstantial evidence suggests that he came from Ohio. His formal name seems to tie him to the Curry family from Wayne County, Ohio (the lumber firm Curry, Cameron & Son, comprised of James Willard Curry and Robert Cameron, formed in 1877); when he left Indiana University, he found work in Cincinnati, Ohio.

The astronomy profession of the mid-twentieth-century had at least this in common with the profession of the nineteenth and twenty-first centuries: success was partly about intelligence and dedication, and partly about who you knew. Letters of recommendation were more informal then than they are now, but a statement of support from a powerhouse astronomer could (can) do much to smooth over a bad patch in a student’s career. A less-than-enthusiastic letter could dog a graduate student for life, arriving in the hands of future employers before he (seldom, she) had a chance to speak for himself.

Astronomer Frank Edmondson depended heavily on the American academic network when filling positions in the Indiana University Astronomy Department and the associated Link Goethe Observatory in Brooklyn, Indiana. He took seriously the recommendations of his fellow astronomers. He consulted the various Directors off Lick Observatory whenever he had a vacancy to fill, whether it be for a postdoc, instructor, junior faculty, or full professor. He was also diligent in his recommendations to his colleagues, possibly to the detriment of poor Bob Cameron.

At the end of 1948, Cameron applied to study at Lick Observatory. Then director, C. Douglas Shane, asked Edmondson about Cameron’s work at IU. Edmondson replied as follows:

Robert C. Cameron was a beginning graduate student here during the academic year 1947-48. He did respectable work during the first semester. However, about the middle of the second semester something happened and he simply stopped working. As a result, he failed in some of his courses and made such low marks in the rest that it was equivalent to failure. He is an assistant at the Cincinnati Observatory this year, and Dr. Herget could tell you how he is getting along now.

Personality and character are OK, and I think you would find him an acceptable member of a small community such as you have on Mount Hamilton. As for his ability and promise as a student, I hesitate to make any predictions. If he has overcome whatever was troubling him last spring, and if a repetition is unlikely, I would rank him a bit above average in ability and promise as a student.[1]

Not surprisingly, Shane didn’t extend a student position to Cameron. Just in case his caution had gone astray in the winter storms, however, Edmondson sent a second letter of dissuasion, noting that

…for the sake of the record I should say that I have talked to Herget recently and there is no reason to believe that Cameron has overcome his personal troubles, whatever they were. Hence, I could not recommend him to you as a student or an assistant.[2]

Try as I might, I have not been able to uncover the nature of Cameron’s “personal troubles.” In February 1949, Cameron was listed as a Student Member of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific.[3] He also attended the Annual Meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Bloomington, Indiana in June 1950.[4] He is listed as first or second author on a series of papers related to minor planet observations made at Goethe Link Observatory in 1949 and 1950 and is credited with the discovery of 1575 Winifred (1950 HH), a Main Belt Asteroid, on April 20, 1950 at Brooklyn, Indiana. Did Edmondson let him come back to IU after he proved he was over his “personal troubles”?

I’ve failed to track Cameron through the 1950s, but in the 1960s, he reappears as an expert on magnetic fields and stars. He shows up as first author of a paper on Babcocks’ star (HD 215441). From there, he advanced to editorial work on books about stellar evolution and magnetic fields. His last publication seems to have been a 1967 edited volume The Magnetic and Related Stars (Proceedings of a symposium, Greenbelt, Md., Nov. 1965), which received several favorable reviews the next year. He died in 1972, a successful enough astronomer that the IAU eventually renamed a small lunar crater (Taruntius C) in his honor.

I’d like to know: was Cameron satisfied in his career? Did he resolve his “personal troubles” to his own satisfaction? Was the discovery of an asteroid enough to make up for being asked to leave Indiana University? Do students ever recover from bad times if those happen to coincide with their years in graduate school? I’m sure many Ph.D. candidates would like to know the answer to that one.

—————

[1] Mary Lea Shane Archives, University of California, Santa Cruz, UA 36 Lick Series 1, Box 83, Letter from Frank K. Edmondson to C. Douglas Shane, 29 January 1949.

[2] Mary Lea Shane Archives, University of California, Santa Cruz, UA 36 Lick Series 1, Box 83, Letter from Frank K. Edmondson to C. Douglas Shane, 13 March 1949.

[3] “Minutes of the Annual Meeting of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, February 2, 1949,” Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, Vol. 61, No. 359, p.114.

[4] Huffer, C. M., “The eighty-third meeting of the American Astronomical Society,” Popular Astronomy, Vol. 58, p.314 (Cameron is #67 in the photo)