S. A. Mitchell with 26-inch refractor. Image courtesy McCormick Museum, University of Virginia

I’ve written before about the dispersal of the book collection that once belonged to Frank K. Edmondson. My wife picked up a couple more of his books for me recently, one of which seems particularly appropriate to discuss at this point in my career.

Book cover, from the collection of Frank K. Edmondson.

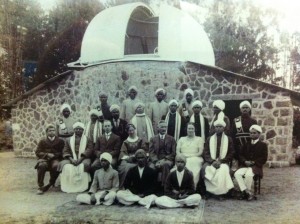

This is a fascinating handbook written in 1947 by Samuel A. Mitchell, director emeritus of the McCormick Observatory at University of Virginia. It’s a modest little book but it makes clear the entangled nature of American astronomy at the beginning of the twentieth century.

Mitchell’s career as an astronomer opened at the Yerkes Observatory, where he “imbibed a small modicum of the research spirit that [he] found there…” [p. 8] He was inspired especially by E. E. Barnard, who had been on staff at Lick Observatory, and Frank Schleslinger, later of the Allegheny Observatory at Pittsburgh. He was impressed by Barnard’s dedication (“If Barnard’s enthusiasm for research could keep him at the telescope with such bitter temperatures [-26 F], why should not I, at the age of 24, not take pattern from the older man?”), but his research trajectory followed that of Schlesinger. [p. 10] As he describes it:

The coming of the photographic plate to the aid of the astronomer and of the largest refractor in the world (dedicated in 1897) brought a great opportunity to ascertain what new information could be found regarding the difficult research of measuring stellar distances. The astronomical world is under a great debt to Professor Frank Schlesinger when he demonstrated in masterful fashion that the parallaxes possibly by photography with the 40-inch Yerkes refractor gave stellar distances with a very great increase in accuracy over the earlier results from visual observations with much smaller telescopes.[p. 13]

Schlesinger’s departure for the Allegheny in 1905 left a gap in the Yerkes program. Mitchell took the opportunity to fill it, beginning his life’s pursuit of the measure of parallax through the use of photography.

The determination of stellar distances through observation and comparative photography formed the core of Mitchell’s research when he became the director of the McCormick Observatory in 1913. Similar efforts were underway at the Allegheny Observatory, where Schlesinger oversaw a 30-inch photographic refractor; at Mount Wilson, where Adriaan van Maanen worked with the 60-inch reflector; at Sproul Observatory (Swarthmore), under John A. Miller with a 24-inch visual refractor; and at Greenwich Royal Observatory with its 26-inch photographic refractor. Charles P. Olivier, native of Charlottesville and later founder of the American Meteor Society, and Harold Alden, arriving from the Yale Observatory in South Africa, joined Mitchell’s efforts at Virginia. [p. 15]

Mitchell arrived at McCormick while on soft money. That is, he “accepted the directorship with no promises from University of Virginia.” [p. 17] Luckily, he was the recipient of the Ernest Kempton Adams Research Fellowship from Columbia University. His fellowship period ended before Virginia decided to pony up some research money, but Edward Dean Adams (father of E. K. Adams, for whom the fellowship was named) decided—after consultation with George E. Hale, once of Yerkes, at the time of Mount Wilson—to give Mitchell a special financial award given the potential significance of his work.

I’m tempted here to start “following the money.” Edward Dean Adams was the president of the Cataract Construction Company, “a new organization of capitalists which ha[d] been formed to furnish electricity and electric power upon a scale of tremendous magnitude by employing the Falls of Niagara to generate the electric fluid.” [see original NYT article here, examine the Edward D. Adams Station Power plant here] Any of you who have driven an International Harvester have used a piece of the Leander McCormick legacy—IH came out of the McCormick Harvesting Machine Company, founded by Leander and his brother, William. McCormick’s planned donation was interrupted by a downturn in his finances after the Great Chicago Fire. So tempting, but I’ll leave the analysis of capital to another time.

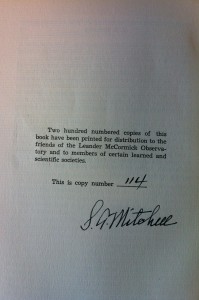

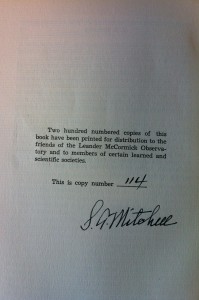

For now, let me just jump forward in time to highlight a few more connections between American astronomers. Mitchell died on February 22, 1960, in Bloomington, Indiana. He was the father of Allan C. G. Mitchell, the chair of IU’s Physics Department, director of the university’s cyclotron program between 1942-44, and colleague of Frank Edmondson. Sadly, Allan Mitchell died young, outliving his father by fewer than the three years (read his obituary here). My question is: did Edmondson acquire this book directly from Samuel Mitchell, perhaps when he moved to Bloomington after his retirement? Or did Allan give it to him? Did he pick it up because he knew and worked with Allan? How did he end up with No. 114 out of a run of 200?

S. A. Mitchell’s signature, back page of handbook

Oh, and why is this appropriate to discuss at this point in my career? I recently accepted a two-year appointment at University of Virginia, which means this little book is making the return trip from Bloomington to Charlottesville via Edison, NJ. I hope someone is keeping track of the movement.